10 Health and Safety Myths – #8 The Hazard Register – What Is It Really For?

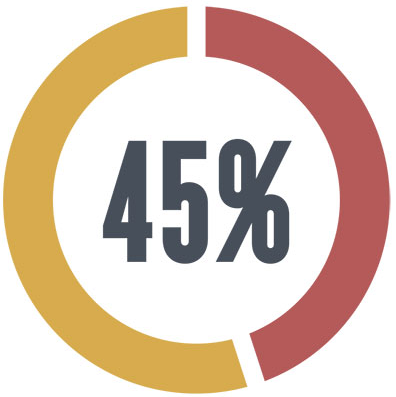

The missing-in-action 45%

Here’s what bothers me about the hazard register and many other health and safety devices. And it’s the reason I am writing this series of ten health and safety myths: In my experience, (which spans more than 30 years in safety systems, mentoring and auditing) – see my safety advice page we can divide employer performance of safety duties into three main categories. I have used personal estimates as follows:

- 50% of employers do nothing or next to nothing in terms of a formal health and safety system. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Because a large proportion of those employers are small and they run a tight operation. And they are often good at being efficient and customer focussed. Which means activities are under active leadership. Formal systems just aren’t critical because there are clear individual responsibilities and a shared purpose. Self-employed people are included in this 50% and they usually know their work blindfolded. They only have themselves and maybe their mate to worry about. But of course, there’s a proportion of ratbags in this 50% who take what they can and do nothing. They hit the headlines with their accidents and they are a headache for the authorities but they probably don’t employ more than 5-10% of all workers.

- 5% of employers have an ethic that clearly views health and safety, (in fact the wider quality framework), as central to their brand and their purpose. So they actually live it. It’s essential. And they usually have a benign but firm people policy. As a result, workers tend to be loyal and enjoy their jobs. Consequently, there is also an environment of fairness and individual responsibility. And it’s likely no one boasts about “safety culture”. Because if you need to put a name on it and gaze at it, you almost certainly don’t have it. Rather, they talk about getting things right, whether it’s delivery, training, product quality or avoiding any form of harm to people or property.

This leaves, (in my estimation), a 45% mixed bag of employers who struggle with health and safety. But in most cases, the official line is that they are going great guns. The worrying thing is that this sector includes a lot of large corporates, so the proportion of workers they represent isn’t 45%. It may be, say, 80% or more of the total population’s workers. They struggle for one or more of the following reasons:

This leaves, (in my estimation), a 45% mixed bag of employers who struggle with health and safety. But in most cases, the official line is that they are going great guns. The worrying thing is that this sector includes a lot of large corporates, so the proportion of workers they represent isn’t 45%. It may be, say, 80% or more of the total population’s workers. They struggle for one or more of the following reasons:

- Process obsession. Managing safety by forms, notices, policies, campaigns and edicts. Personal leadership and creative communication are rare or absent. A facade behind which directors, senior managers and safety people expend significant resources and play games to achieve disproportionately little. As thin as an oil slick.

- Lip service only. A safety person who wears 2 other hats is left to their own devices. They are there to get the monkey off the back of people who should be leading.

- Magic Wand Brigade. Similar to process obsession, but worse. If a dusty manual exists and someone once wrote a Hazard Register, all we need to do is drag it out, show the inspector/auditor and point at things.

- The Wayward Safety Person. Dead keen, somewhat annoying but at the same time likeable in small doses. Full of ideas that can never be fulfilled. Always working on the next big thing but just can’t get around to the simple stuff. Often linked with item 2 above. Always gets onto the next safety buzzword because it will be the answer to everything. Looks lonely and lost at times.

What’s that got to do with the Hazard Register?

Simply that it appears there are misconceptions about the purpose and value of the Hazard Register. These misconceptions have a distinct affinity with items 1, 2 & 3 above. And hazard registers are often poorly put together. As a result, safety systems can look like smoke and mirrors.

Here are four misuses of the Hazard Register:

- A Hazard Register is somehow an end in itself. By producing one, you have ticked a box. The Act and Regulations don’t require a hazard register. But we ought to record in writing how our current hazards are mitigated.

- By hanging it on the wall, workers will read it and learn. Actually, nobody does believe this but we feel we have a duty to display it. However, apart from Murray or Kate, who are fastidious and attentive, no one will be reading that hazard register. What matters is that if the hazard register specifies, say, a guard to manage the risk, then you have to have a guard and you need to inspect and supervise routinely to ensure it stays. If it needs training, you train and supervise people. Restrict some types of work to specially trained people. And you verify their competence and give refresher training for critical skills. All this ought to be documented. As long as relevant people are trained in “SOP 23”, it’s fine for the hazard register to refer to it. So training records are important. Take tangible actions. None of this “just happens” by hanging a Hazard Register on the wall.

- Once you have a Hazard Register, it’s set in stone. On the contrary. A Hazard Register is just a line in the sand. It’s how we do things today. Identify new hazards by learning from mistakes, inspections, audits, reviews and discussions. Existing risk controls may be improved through new technology, better understanding or investigation of errors.

- Generalities: “Use appropriate PPE”; “Take care while lifting”; “Follow manufacturer’s instructions“. This is opting out of responsibilities. It’s a form of procrastination for when we really don’t have a clue. But we have a duty to be specific. There is no excuse for retreating into the shadows and leaving workers on the front line with no clear idea of what to do.

Residual Risk

I’m all for Hazard Registers. But if we are serious about it, and we record any form of risk assessment, think carefully about the potential consequences (no pun intended). Because high risk-ratings against a hazard indicate that either the current likelihood or current severity, (more likely both), are high. So, should anyone be exposed to that hazard? Because it doesn’t appear to have been dealt with, does it? Remember, you should have done what was “reasonably practicable”, and applied the hierarchy of controls, starting with the most effective categories and working down. The risk rating should, by now, reflect the risk level under the current controls that you are presumably happy with, at least for now. Residual risk is using current control measures. No point in assessing the hazard “as if” no controls are in place. Apart from anything else, we might be incriminating ourselves.

I’m all for Hazard Registers. But if we are serious about it, and we record any form of risk assessment, think carefully about the potential consequences (no pun intended). Because high risk-ratings against a hazard indicate that either the current likelihood or current severity, (more likely both), are high. So, should anyone be exposed to that hazard? Because it doesn’t appear to have been dealt with, does it? Remember, you should have done what was “reasonably practicable”, and applied the hierarchy of controls, starting with the most effective categories and working down. The risk rating should, by now, reflect the risk level under the current controls that you are presumably happy with, at least for now. Residual risk is using current control measures. No point in assessing the hazard “as if” no controls are in place. Apart from anything else, we might be incriminating ourselves.

Hazard vs. Risk

Don’t get distracted by the HASAW Act apparently upping the profile of the word “risk”. The Act uses the word “hazard” 115 times and the word “risk” 137 times. So, to cut a long story short, a hazard is still something with potential to cause harm, even though that part of the definition has now been removed. Risk is not even defined, but it’s a way of quantifying. Therefore, it’s an appendage to a hazard. Same as fuel consumption ratings are an appendage to a car. You can touch a car, but you can’t touch a fuel consumption rating. If a guard falls off a machine, the hazard has not changed, but the risk just went up. And you can’t touch the risk. You can only touch the hazard. But don’t.

To understand the role of risk in your duties under the Act, you need to go no further than the definition of what is “reasonably practicable” to do. The first two considerations require consideration of 1. “How likely” and 2. “The Degree of harm”. This was essentially the same under the last Act and it’s purely and simply a risk assessment. I personally find the current use of “risks”, as discreet objects rather distracting. But it is what it is.

Contact me if I can help you with any safety stuff. Call 0800 000 267 for a welcoming chat, or email simon@safetypro.co.nz

- Simon Lawrence is Director of SafetyPro Limited.

- Consulting for safety: Safety Advice, Problem Solving, Audits and Training

- Call 0800 000 267 for a welcoming chat, or email simon@safetypro.co.nz

My 10 Health & Safety Myths. Planned topics and dates.

-

- # 1: Passion for Safety – Please no! 29 August 2019

- #2 Lost Time Injury Rates – Dark Arts in the Boardroom. 18 September 2019

- #3 Zero Harm – Stop Taking it Literally! 9 October 2019

- #4 We Have a Safety Culture – Yeah. Nah! 30 October 2019

- #5 Safety Audits – Smoke and Mirrors 20 November 2019

- #6 Safety Manuals – You’d Think it Would be Simple 31 January 2019

- #7 Safety Policy Statements – You Are Committed to What? 21 February 2020

- #8 The Hazard Register – What Is It Really For? 7 August 2020

- #9 Accident Investigation – Tick & Flick 28 August 2020

- #10 Contractor Management – The Thin Paper Wall 18 September 2020

Check out our SafetyBase software

- View a 4 minute video overview. Please like or share.

- Browse the SafetyBase website.

- Short cut to the all-important Pricing Page. No hidden costs.

- Download a PDF Fact Sheet to show to your Senior Leadership Team.

Call me, Simon, on 0800 000 267 or email simon@safetypro.co.nz You could be trying out this highly effective health and safety software system in minutes